La version française suit….

February 21, 2024

Dear Ministers Guilbeault and Wilkinson,

Canada is unique among OECD countries in giving its national regulatory agency sole responsibility for decisions about nuclear waste disposal projects. This is unacceptable to Canadians.

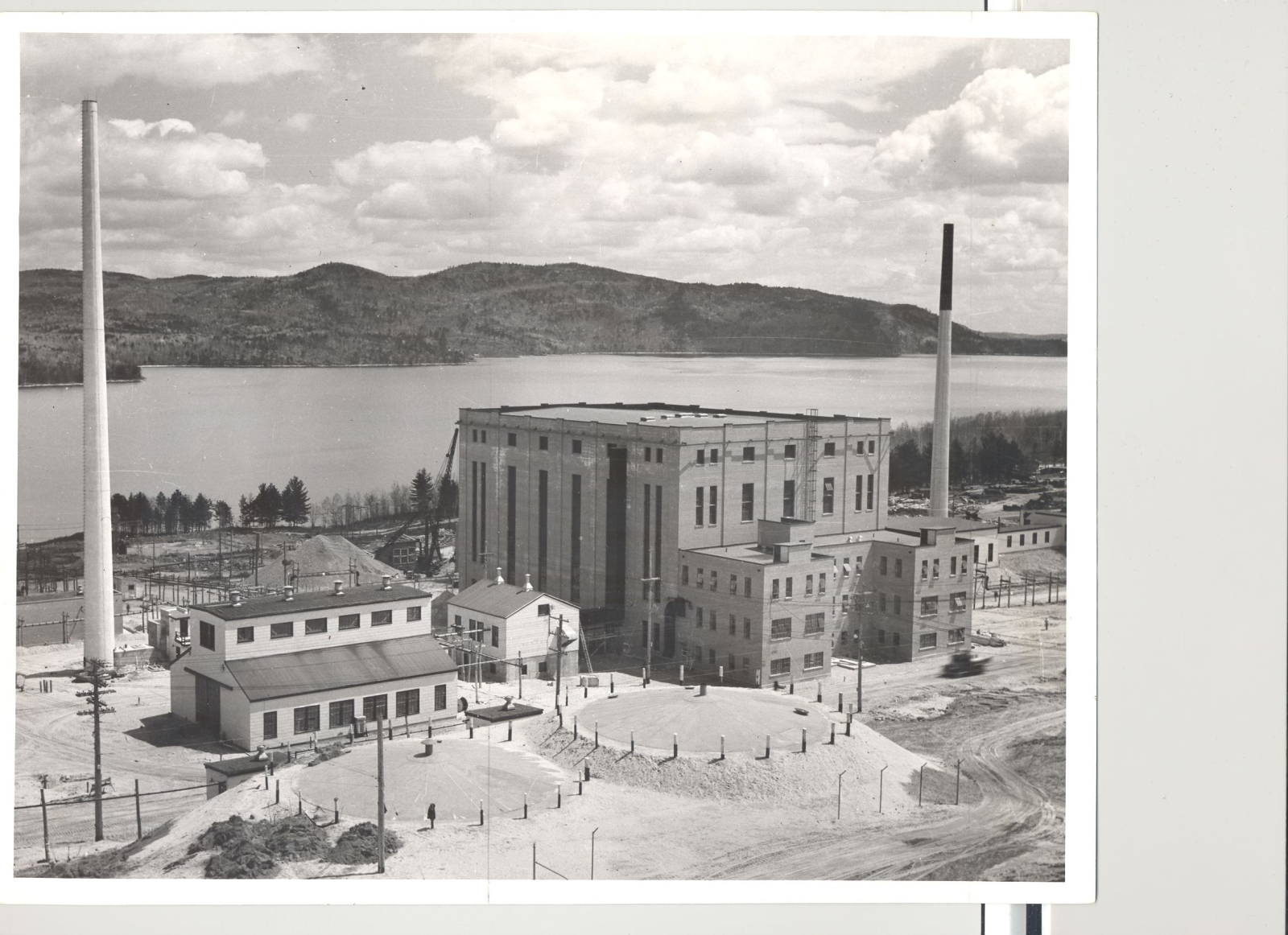

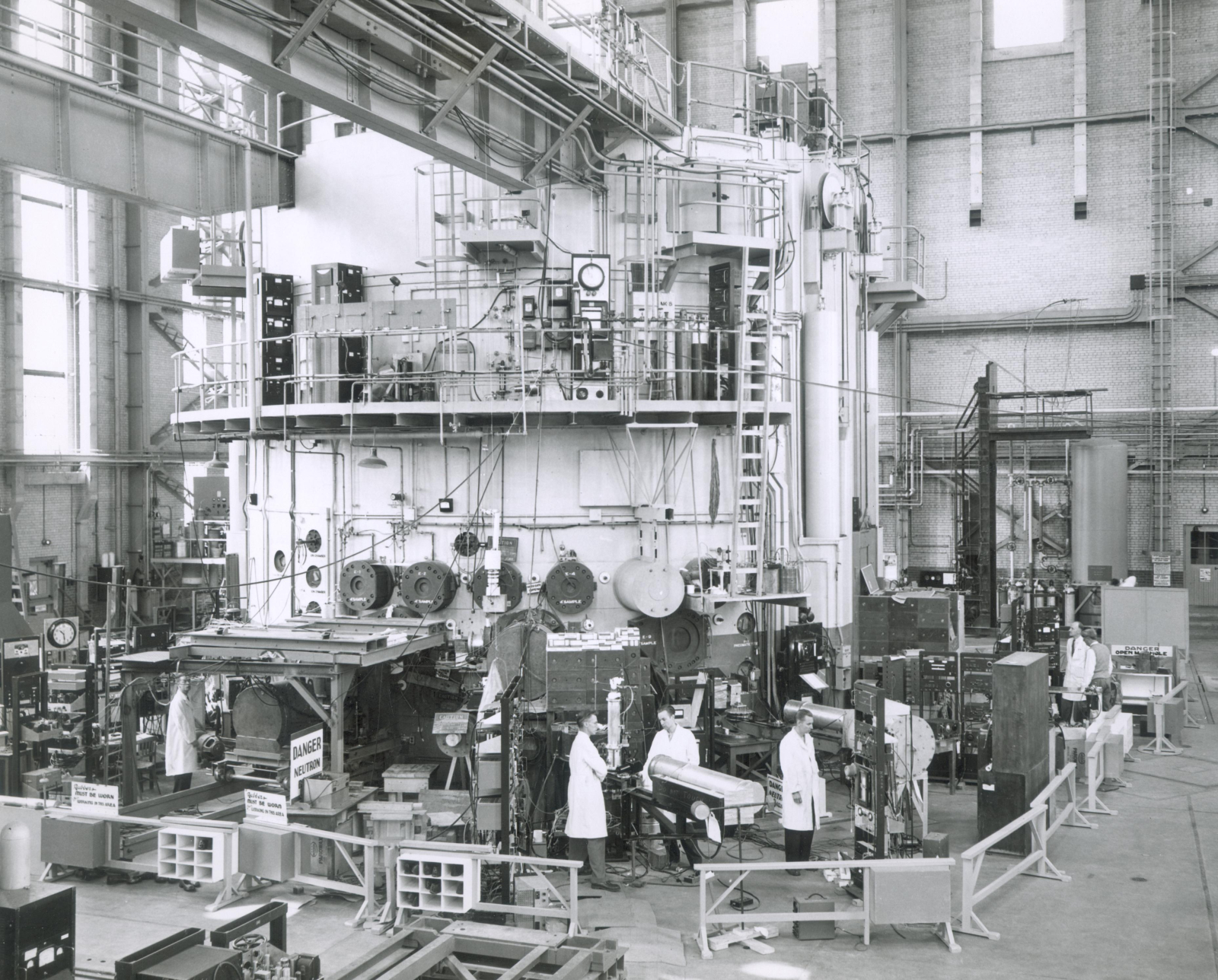

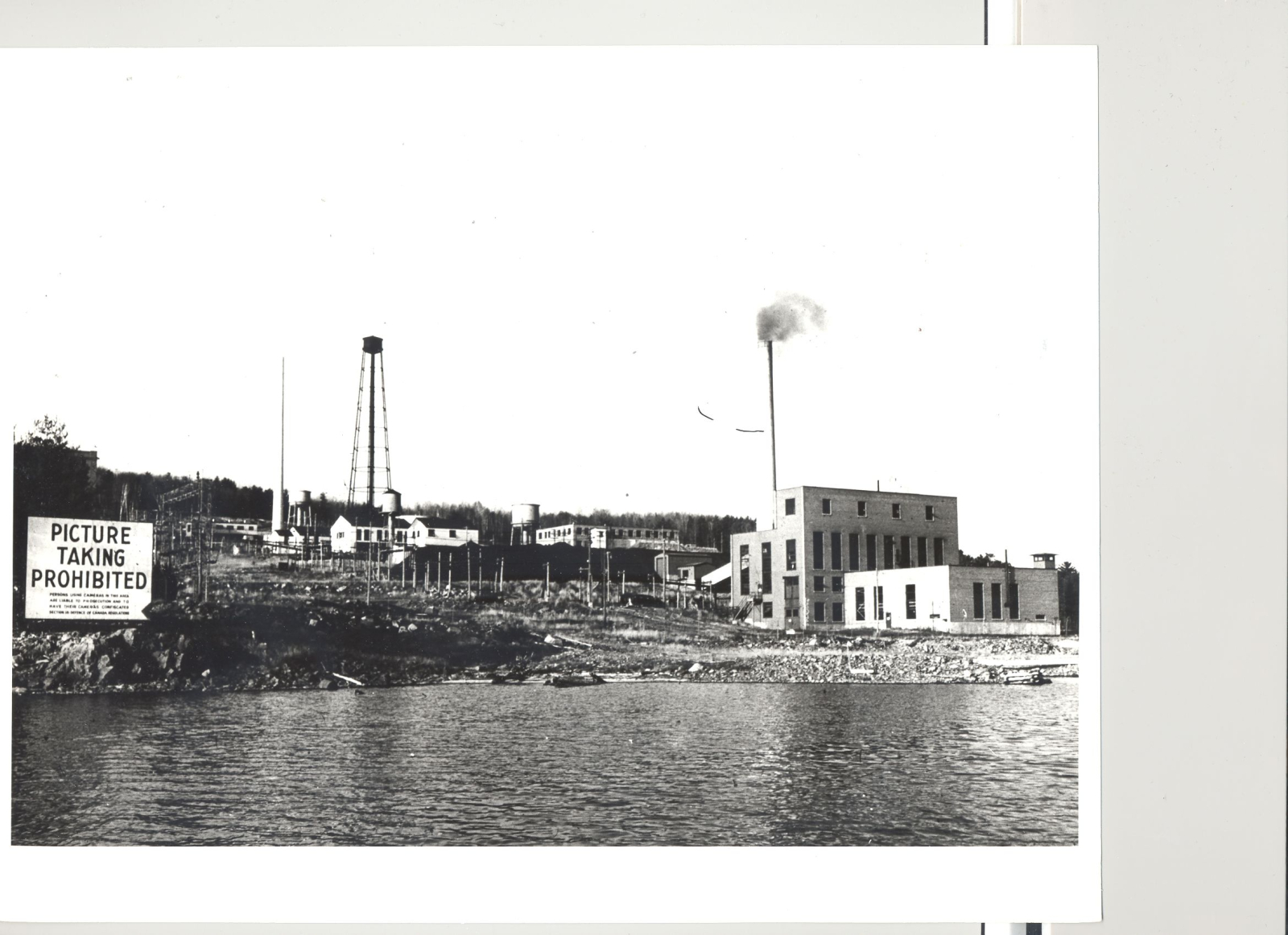

The Near Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) is a proposed disposal facility for radioactive waste at the federally owned Chalk River Laboratories site. The NSDF project was approved by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) on January 9, 2024.

On February 16, 2024, Mme Monique Pauzé (Repentigny, BQ) asked the following question in the House of Commons:

“Given that there is no social licence for the Chalk River Project, will the minister reverse the decision?”

The feds are the ones are jeopardizing Quebec’s drinking water with a nuclear dump. Will the government stop hiding and say no to Chalk River?

Marc Serré, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Natural Resources, replied:

“The government is not the one deciding on these projects. Canadians do not want politicians to decide on these projects.”

Canadians want to know that there are experts who will study the decision and carry out consultations. Canadians have made it clear that they do not want politicians making this decision.

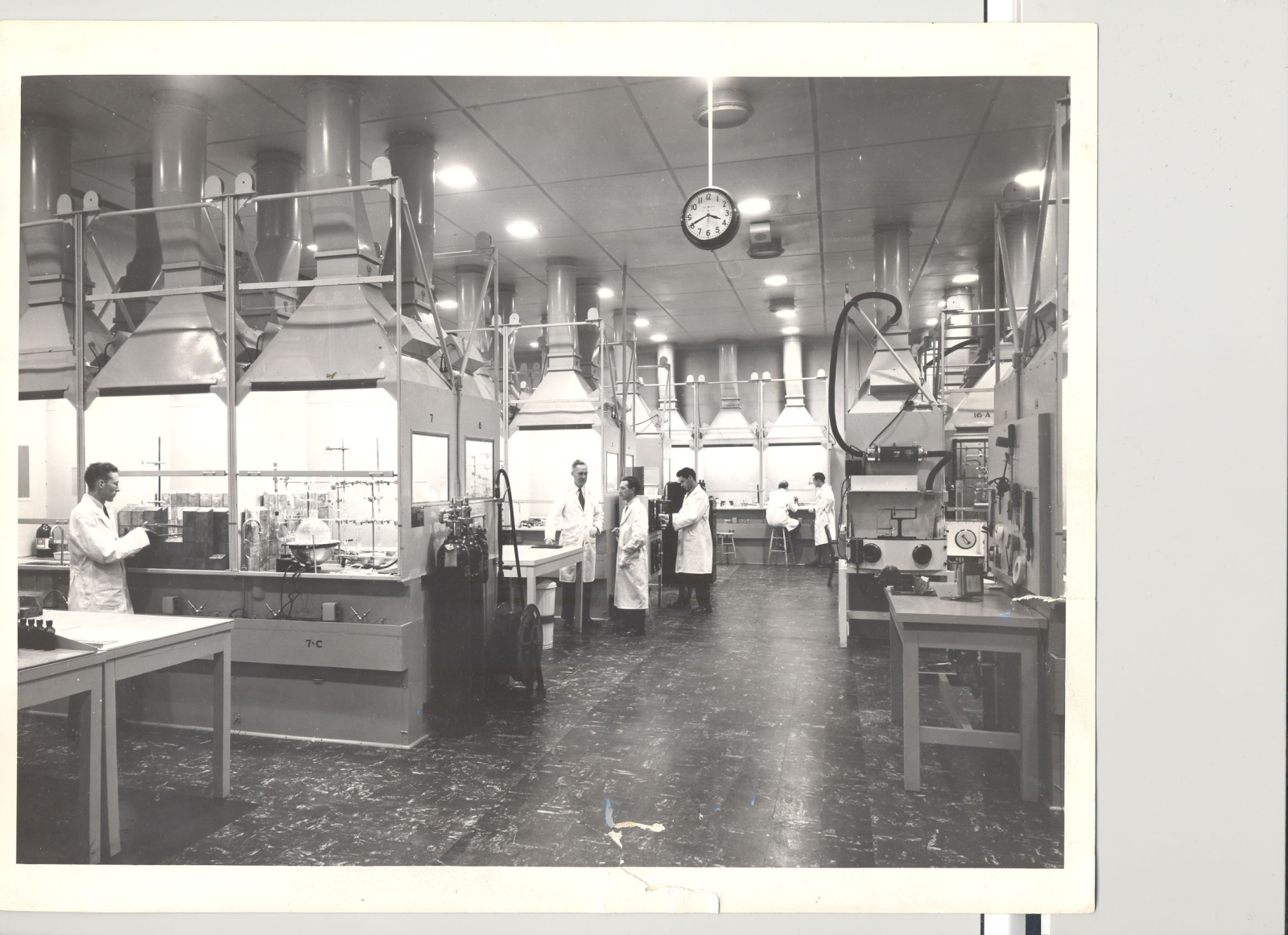

However, radioactive waste experts who worked at the Chalk River Laboratories and studied the NSDF project in detail warn that it is unsafe.

Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians want elected officials and the Government of Canada to be accountable for decisions on the NSDF and other nuclear waste disposal projects.

On January 29, 2024, MP Sophie Chatel (Pontiac, Liberal Party) presented e-petition 4676 to the House of Commons. Signed by 3127 Canadians, it calls on the Government of Canada to order the CNSC to make no decision on licensing of a radioactive waste disposal facility unless Canada’s obligations under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) are met.

On February 14, 2024, the Kebaowek First Nation, along with the Bloc Québécois, organized a press conference to demand that the Government of Canada put an end to the Near Surface Disposal Facility Project. The press conference was attended by leaders of several other Algonquin First Nations who have never ceded the land on which the NSDF would be built. Nor have these nations given their free, prior and informed consent to the project, as required by article 29, paragraph 2, of the UNDRIP.

The CNSC is an unelected body that is not accountable to the electorate. It has neither the expertise nor the mandate to determine whether the NSDF has met UNDRIP requirements and obtained the necessary social license from Canadians. From a strictly technical point of view, the regulator is faced with a very difficult problem: How to ensure the safety of human beings and the environment for the next ten millennia?

It is the Government of Canada, not the CNSC, that must comply with the UNDRIP. The CNSC is not qualified to implement UNDRIP. The UNDRIP action plan does not apply to the CNSC. The assessment and authorization of a radioactive waste site should not be entrusted to a body that is not accountable to Indigenous peoples or to the public.

CNSC impact assessment (IA) processes lack public trust. A 2017 Expert Panel Report, Building Common Ground: A New Vision for Impact Assessment in Canada, said:

“To restore public trust and confidence in assessment processes, the conduct of IAs must respect the principles of being transparent, inclusive, informed and meaningful. Any authority given the mandate to conduct federal assessments should be aligned with these principles…”

After the creation of the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada in 2019, assessments done by the National Energy Board (NEB) were transferred to the Agency. However, the CNSC continues to act as a “responsible authority” (RA) that conducts its own assessments for projects that it regulates, such as the NSDF.

In 2017, the Expert Panel noted several concerns about assessments conducted by the CNSC (and the NEB):

…there is a perception of a lack of independence and neutrality because of their close relationship with the industries they regulate. For example, participants noted the cross mobility of personnel between these regulators and their regulated industries and voiced concerns that these RAs promote the projects they are tasked with regulating.

CNSC’s sole authority to assess and license nuclear waste disposal projects has resulted in the absence of social licence for the NSDF project, as Mme Pauzé observed.

On this matter, the Expert Panel’s report seems almost prophetic:

Public trust and confidence is crucial to all parties. Without it, an assessment approval will lack the social acceptance necessary to facilitate project development. While some would likely favour the NEB and CNSC for the assessment of projects in their particular industries, the erosion of public trust in the current assessment process has created a belief among many interests that the outcomes are illegitimate. This, in turn, has led some to believe that outcomes are pre-ordained and that there is no use in participating in the review process because views will not be taken into account. The consequence of this is a higher likelihood of protests and court challenges, longer timeframes to get to decisions and less certainty that the decision will actually be realized – in short, the absence of social license.

In all OECD countries except Canada, decisions on the disposal of radioactive waste are the responsibility of government agencies, and in many cases, more than one. Canada is the only country to give its regulator, the CNSC, sole and final decision-making authority in this area, according to the document “The Regulatory Infrastructure in NEA Member Countries,” published by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA).

In the U.S. and U.K., environment agencies are given decision-making power in respect of nuclear waste disposal. In the case of the NSDF, it appears that Environment and Climate Change Canada has decision-making power because of the requirement for a permit to destroy habitat for species at risk.

The government could ask the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to carry out an ARTEMIS review. ARTEMIS reviews are carried out by competent peers, available to all IAEA member states. An ARTEMIS review could provide the Government of Canada with valuable advice on how to manage its legacy radioactive waste.

We have the following three requests:

- No disposal of radioactive waste until Canada has met its UNDRIP obligations;

- No permits to destroy habitat for species at risk at the NSDF site; and

- An international ARTEMIS review of long-term management of the Government of Canada’s radioactive waste.

Yours sincerely,

Ginette Charbonneau, Ralliement contre la pollution radioactive

Gordon Edwards, Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility

Ole Hendrickson, Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County and Area

—————————

Le 21 février 2024

Messieurs les Ministres Guilbeault et Wilkinson,

Le Canada est le seul pays de l’OCDE qui confie à la CCSN, son agence nationale de réglementation, la responsabilité exclusive des décisions relatives aux projets d’élimination des déchets radioactifs. Cette situation est inacceptable pour les Canadiens.

Le Projet d’installation de gestion des déchets près de la surface (IGDPS) est un projet d’élimination permanente de déchets radioactifs sur le site des Laboratoires nucléaires de Chalk River, propriété du gouvernement fédéral. Le projet a été approuvé par la Commission canadienne de sûreté nucléaire (CCSN) le 9 janvier 2024.

Le 16 février 2024, Mme Monique Pauzé (Repentigny, Bloc Québécois) a posé les questions suivantes à la Chambre des communes :

Puisqu’il n’y a pas d’acceptabilité sociale pour le projet de Chalk River, est-ce que le ministre va annuler cette décision?

C’est le fédéral qui met en péril l’eau potable des Québécois avec un dépotoir nucléaire. Le gouvernement va-t-il cesser de se cacher et dire non au projet de Chalk River?

Marc Serré, secrétaire parlementaire du ministre des Ressources naturelles, a répondu :

Ce n’est pas le gouvernement qui décide de ces projets. Les Canadiens ne veulent pas que les politiciens décident de ces projets.

Les Canadiens veulent savoir que ce sont des experts qui vont étudier la décision et qui vont faire les consultations. Les Canadiens sont clairs: ils ne veulent pas que ce soient des politiciens qui prennent cette décision.

Cependant, des experts en déchets radioactifs qui ont travaillé aux Laboratoires de Chalk River et qui ont étudié en détail le projet d’IGDPS concluent qu’il n’est pas sécuritaire.

Tous les Canadiens, autochtones et non autochtones, veulent que les élus et le gouvernement du Canada soient responsables des décisions sur l’IGPDS et sur les autres projets d’élimination de déchets radioactifs.

Le 29 janvier 2024, la députée Sophie Chatel (Pontiac, Parti Libéral) a présenté la pétition 4676 à la Chambre des communes. Elle était signée par 3127 Canadiens qui demandent au gouvernement d’ordonner que la CCSN n’autorise aucune installation de stockage de déchets radioactifs sans que le Canada n’ait respecté la Déclaration des Nations Unies sur les droits des peuples autochtones (DNUDPA).

Le 14 février 2024, la Première nation Kebaowek a organisé avec le Bloc Québécois une conférence de presse pour demander que le gouvernement du Canada mette fin au Projet d’installation de gestion des déchets près de la surface. Cette conférence de presse s’est tenue en présence des dirigeants de plusieurs autres Premières nations algonquines qui n’ont jamais cédé leur territoire sur lequel l’IGDPS serait érigée. Ces nations n’ont pas donné non plus leur consentement libre, préalable et éclairé au projet, contrairement à ce que demande l’article 29, paragraphe 2, de la DNUDPA.

La CCSN est un organisme non élu et qui n’est pas responsable devant l’électorat. Elle n’a ni l’expertise ni le mandat pour déterminer si l’IGDPS a satisfait aux exigences de la DNUDPA et a obtenu l’acceptabilité sociale nécessaire de la part des Canadiens. Même d’un point de vue strictement technique, l’autorité de réglementation est confrontée à un problème très difficile : Comment assurer la sécurité des êtres humains et de l’environnement pour les dix prochains millénaires?

C’est le gouvernement du Canada, et non la CCSN, qui doit se conformer à la DNUDPA. La CCSN n’est pas qualifiée pour appliquer la DNUDPA. Le plan d’action de la DNUDPA ne la concerne pas. On ne doit pas confier l’évaluation et l’autorisation d’un site de déchets radioactifs à un organisme qui n’a aucun compte à rendre aux peuples autochtones, ni au grand public.

Les évaluations d’impact environnemental de la CCSN n’ont pas la confiance du public. La Rapport du Comité d’experts, Bâtir un terrain d’entente : une nouvelle vision pour l’évaluation des impacts au Canada, concluait :

Afin de restaurer la confiance du public, les évaluations d’impact doivent être transparentes, inclusives, éclairées et significatives. Toute autorité qui reçoit mandat de mener des évaluations fédérales devrait respecter ces principes…

Depuis la création de l’Agence d’évaluation d’impact du Canada en 2019, celle-ci assume toutes les évaluations qui relevaient auparavant de l’Office national de l’énergie (ONE). Par contre, la CCSN continue d’être une “autorité responsable” qui effectue ses propres évaluations sur les projets qu’elle réglemente, dont le projet d’IGDPS.

En 2017, le groupe d’experts a relevé plusieurs préoccupations envers les évaluations de la CCSN (et de l’ONE) :

…on perçoit un manque d’indépendance et de neutralité à cause de leur étroite relation avec les industries qu’ils réglementent. Des participants ont noté par exemple la mobilité du personnel entre ces organismes de réglementation et le secteur industriel qu’ils règlementent. Ils sont inquiets quand ils voient ces organismes faire la promotion des projets qu’ils doivent réglementer.

Le fait que la CCSN soit seule pour évaluer et autoriser les projets d’élimination des déchets radioactifs enlève toute acceptabilité sociale au projet IGDPS, souligne Mme Pauzé.

À cet égard, le rapport du groupe d’experts semble prophétique :

La confiance du public est cruciale. Sans elle, aucune approbation ne recevra l’appui social requis pour que le projet se réalise. Plusieurs secteurs industriels préfèrent que leurs projets soient évalués par l’ONE et par la CCSN mais cela entraîne une telle perte de confiance du public que les conclusions de ces évaluations ne semblent plus légitimes. Certains croient que les résultats sont déterminés d’avance et qu’il est inutile de participer au processus d’évaluation puisque leurs points de vue ne seront pas pris en compte. Cela entraîne des risques accrus de protestations, de contestations judiciaires, de procédures qui s’éternisent et cela mène à douter de la mise en œuvre des décisions. Bref, absence d’acceptabilité sociale.

Dans tous les pays de l’OCDE, sauf au Canada, les décisions sur l’élimination des déchets radioactifs relèvent des organismes gouvernementaux et même de plusieurs organismes bien souvent. Le Canada est le seul pays qui donne à la CCSN un pouvoir de décision unique et final dans ce domaine, révèle le document “The Regulatory Infrastructure in NEA Member Countries,” publié par l’Agence de l’OCDE pour l’énergie nucléaire (NEA).

Aux États-Unis et au Royaume-Uni, les ministères de l’environnement ont un pouvoir décisionnel sur l’élimination des déchets nucléaires. Dans le cas de l’IGDPS, il semble qu’Environnement et Changement climatique Canada pourrait aussi avoir un vrai pouvoir de décision puisque ce ministère doit autoriser toute destruction de l’habitat des espèces en péril.

Le gouvernement pourrait demander à l’Agence internationale de l’énergie atomique (AIEA) de procéder à un examen ARTEMIS. Les examens ARTEMIS sont effectués par des pairs compétents, disponibles pour tous les États membres de l’AIEA. Un examen ARTEMIS pourrait fournir au gouvernement du Canada des conseils précieux sur la manière de gérer ses déchets radioactifs hérités.

Nous formulons les trois demandes suivantes:

- Aucune élimination de déchets radioactifs tant que le Canada n’aura pas satisfait à ses obligations au titre de l’UNDRIP ;

- Aucun permis de détruire l’habitat des espèces en péril sur le site de l’IGPDS ; et

- Tenue d’un examen international ARTEMIS sur la gestion à long terme des déchets radioactifs du gouvernement du Canada.

Nous vous prions d’agréer l’expression de nos sentiments distingués,

Ginette Charbonneau, Ralliement contre la pollution radioactive

Gordon Edwards, Regroupement pour la surveillance du nucléaire

Ole Hendrickson, Citoyens inquiets du comté de Renfrew et de sa région